COP28: The importance of the question

Newsletter #41

Photo: Kiara Worth for UN Climate

Much has been said about COP28, and a lot of the media coverage is dominated by a focus on the “historic” character of the first-ever mention of fossil fuels in the Global Stocktake “flagship” text, which signals the end of an era.

This either/or is a typical default of the media, but it illustrates a deeper misunderstanding of how the COP process has evolved since 2015. Take this question from The Times Environment Editor to his followers on Linked In:

The media, are of course, a vital piece in what some experts call the “performance” or “dramaturgy” of the post Paris-COPs, which marked the transition away from legally binding frameworks to voluntary commitments.

In the current era, COPs are, according to climate governance expert Stefan Aykut, “increasingly staged as signals for a global audience. The strongest signal is commonly believed to come from the final decision.”

One way to make sure that the signal lands effectively, is through the staging of the event. (In 2015, legend has it that COP21 President Laurent Fabius and Environment Minister Segolene Royale argued bitterly for months to agree a colour for the wallpaper at Le Bourget). The UAE Presidency hired armies of PRs and consultants to use this event to bolster their soft power and deepen the image of themselves as some kind of eco-futurist model - and, in many ways, it worked.

Visual branding

Photo: Kiara Worth for UN Climate

Part of the seduction campaign came down simply to the visuals of the event: the traditional shots of diplomats in rooms either arguing or celebrating were offset by idyllic outdoor tents, palm trees - climate negotiators, NGOs, media and lobbyists in a balmy, corporate kind of Burning Man. There was a less of a sense of “us and them”, and even the traditional North-South face-offs were muted by the UAE staging.

For example, a lot of the impromptu conversations at COPs typically take place as people sprint from one pavillion to another - but here the pavillions were islands unto themselves, separate rooms. Less contact, less friction?

Success vs failure

The success vs failure narrative of mainstream media coverage tends to limit a deeper appreciation of the value of such mega-events.

If COP28 was a music festival, we could say it worked because more people came than ever before - nearly 100,000 badges were issued, almost doubling the number of participants who went to Sharm El Sheikh last year for COP27, the previous largest.

If COP28 was a trade fair, it was a winner because of the excellent logistics - nobody complained about difficulty getting food and water (which was the case at Sharm El Sheikh), the venue was vast, but golf carts were available to seamlessly convey delegates from one panel discussion to another.

Photo: Kiara Worth for UN Climate

But on the content of the outcome, things get fuzzy.

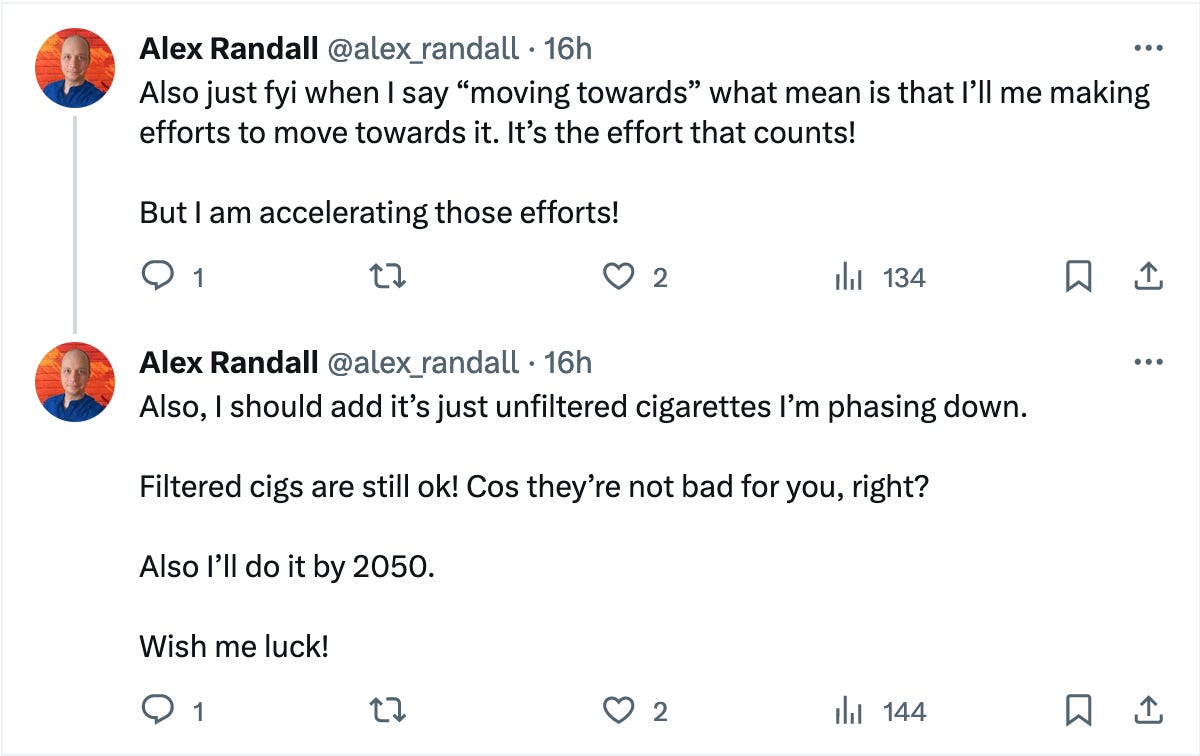

This parody on X sums up the position of the “failure” narrative.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember when evaluating any COP is to go back to what it is, and what it is designed to achieve.

One way to think about any Conference of the Parties is as a giant committee meeting. It’s easy to criticize such a process if your starting point is: this process should solve global problems and ignite transformative change.

Stefan Aykut, the climate governance expert mentioned above, offered this analysis in a thread on X.

So what can #COP28 achieve? It is important to acknowledge that in a world as divided as ours, a COP cannot solve all global problems. COPs cannot be at the forefront of debates. They only formalize what national publics & politics are willing to concede.

What COPs can do, however, is to contribute to ongoing processes of change & support local action & national struggles through global targets, legal norms, political agenda setting & media attention.

French economist Maxime Combes also shared a helpful thread reminding us that there are multiple ways to analyse the outcome of this COP, notably the second point below, which says “the paragraph (referring to fossil fuels in the Global Stocktake) is the (implicit) acknowledgement that the silence in the Paris Agreement on fossil fuels is unacceptable and problematic”.

He recalls that a COP decision does not have the force of an international treaty, and therefore the reference to a transition out of fossil fuels does not require any member state to limit or ban exploration or exploitation of fossil fuels on their territory.

To sum up, a key insight from Stefan Aykut’s work is the fact that since COP21 in Paris, climate summits are “not only designed to produce legal text, but also at crafting narratives and symbols to influence the expectations of politicians, investors & civil societies.”

👉 In this new system, COP Presidencies have an important role: they can shape the dramaturgy of a COP by using their formal prerogatives on agendas, communication and design of the venue.

The proof of success for the UAE from this perspective? Look at President Sultan Al Jaber’s expression in the photo below.

Photo: UN Climate; Sultan Al Jaber, COP28 President; Simon Stiell, UNFCCC Executive Secretary

Thanks for reading. It’s been a busy end of year, and I’m taking stock of where the newsletter is heading in 2024. I would love to hear from you on what you’ve enjoyed, and what you’d like to see more of, so please do take a minute to hit reply with your feedback, or leave a comment.

Happy holidays and see you in January 2024.